Chapter 5Lists and Recursion

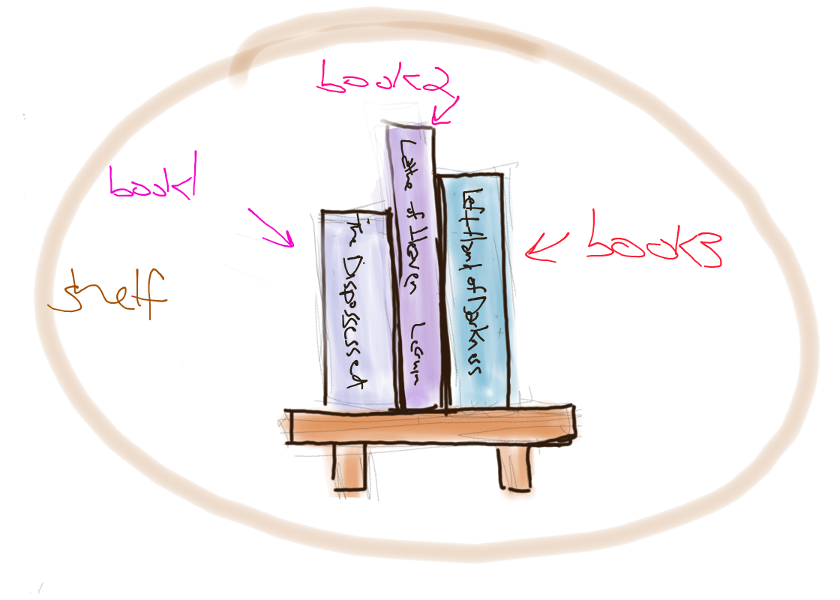

In the objects chapter, we looked at books as an example of data modeling with objects:

var disposessed = { title: "The Disposessed" , author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }

How do you model a bunch of books? You could say:

var bookshelf = { book1: disposessed , book2: latheofheaven , book3: lefthandofdarkness }

But there are some problems with this. Some people have a LOT of books. They add books to their bookshelves all the time (and could, theoretically, remove them as well). At any given moment, they might not know exactly what’s on their shelf. So they want to be able to ask: how many books do I have? where on the shelf are they? do I have a copy of Watchmen? to whom did I lend my copy of Pedagogy of the Oppressed? For all but the last, we can answer these questions with a program! (We could make a lending library program if we wanted to answer the last as well, but we’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader!) But to answer questions about collections like this, we need to structure the data very differently from the example above.

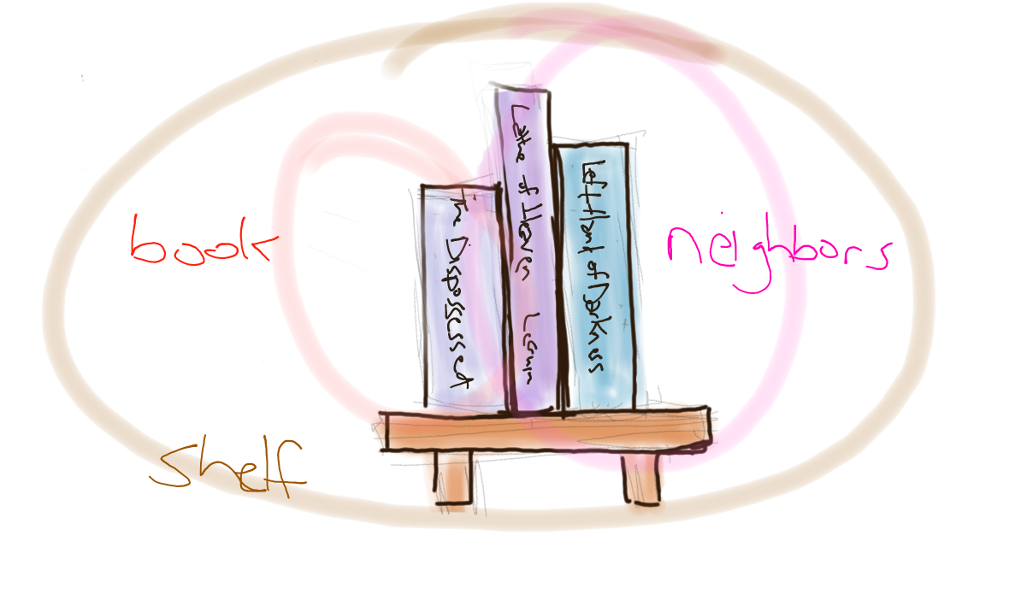

So, lets try structuring the data differently. One way to do that is to think about how the books are arranged. We start with one book, then say how the other books are arranged in relation to that book. The left-most book on my bookshelf is The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Leguin.

This book has neighbors to the right — starting with The Lathe of Heaven by the same author.

var books = { book: { title: "The Disposessed", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: { book: { title: "Lathe of Heaven" author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } } } };

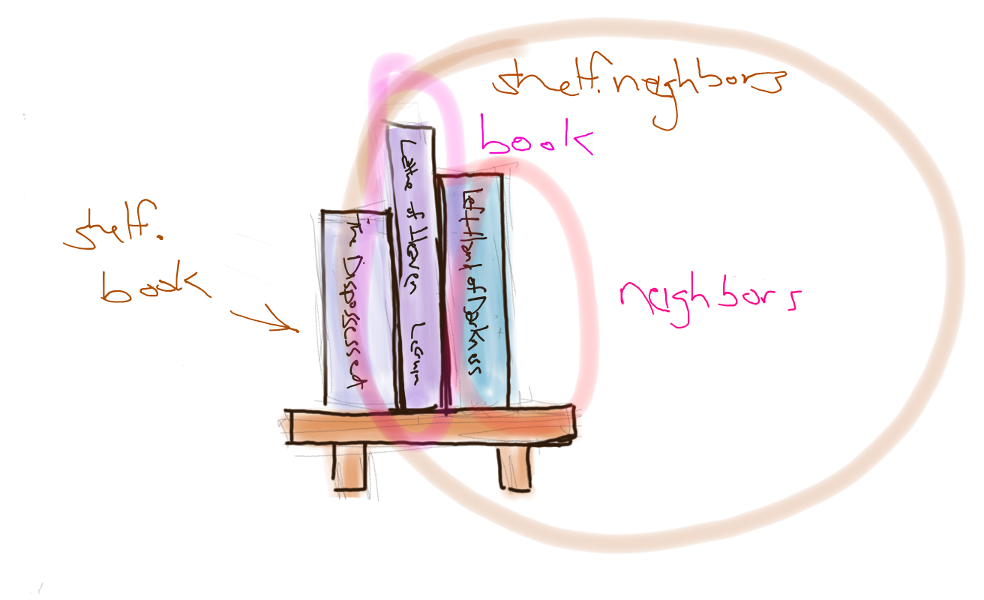

But does Lathe of Heaven have a right-hand neighbor on the shelf? Of course, The Left Hand of Darkness!

var books = { book: { title: "The Disposessed", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: { book: { title: "Lathe of Heaven", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: { book: { title: "Left Hand of Darkness", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } } } } };

This is a very short bookshelf that only holds my very favorite Ursula

K. LeGuin books, so that’s it. The Left Hand of Darkness has no

right-hand neighbor. But all the other books have a neighbor field, so

The Left Hand of Darkness should have one too. It’s shortly

going to be very important that every "layer" of this object have the

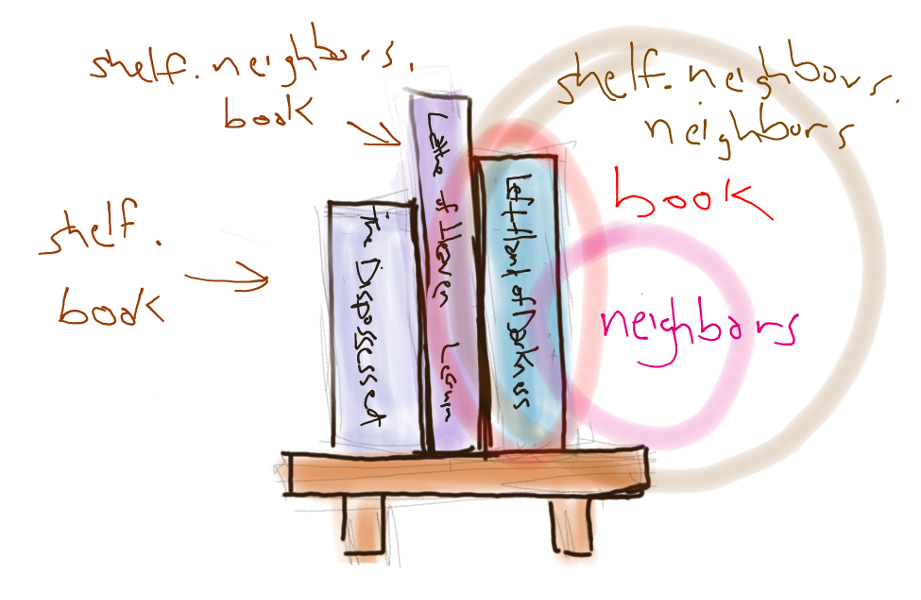

same fields! So shelf.neighbors.neighbors.neighbors is going to be a

special value to represent that there is no book there.

var endOfShelf = {} // an empty object, named for clarity! var books = { book: { title: "The Disposessed", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: { book: { title: "Lathe of Heaven", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: { book: { title: "Left Hand of Darkness", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: endOfShelf } } } };

Now if we want to know what is to the right of a book, we just have to

look at the neighbors field. shelf.book is definitely the first book

in my shelf. and shelf.neighbors.book is the next. I can keep going

(shelf.neighbors.neighbors.book) until I find endOfShelf and know

that I’ve seen all the books. But what does "seeing all the books"

look like in code?

Counting Books

For an example, let’s use the design recipe to write a function to count all our books!

First thing is the signature. What is a shelf?

The signature for a book is this:

// { title: string, author: {first: string, last: string }

// { book: { title: string, // author: { first: string, last: string } }, // neighbors: {book: { title: string, // author: { first: string, last: string } }, // neighbors: { book: ...wait...???????

This signaure seems different from other object signatures. To describe my shelf of Ursula LeGuin novels, we’d need three nested objects representing three books. But we don’t want to describe just my shelf as it is right now — this structure should apply to ANY shelf, whether it has no books or 3 books or 30 books or even more. So it seems like our nested signatures could just go on and on forever — or, if it’s empty, it could end right where it starts!

How can we describe this odd object?

First, we can give the whole object structure a name, then refer to it by name within the structure itself.

Secondly, we can say the structure could be a different sort of object — we add an "OR". A shelf is an emptyShelf "OR" this more complicated structure.

// shelf = emptyShelf OR { book : { title: string, // author : {first: string, last: string} }, // neighbors : shelf }

A data structure that refers to itself is called a recursive data structure.

Now we can finish the countBooks function signature by saying what kind of value we expect back:

// shelf = emptyShelf OR { book : { title: string, // author : {first: string, last: string} }, // neighbors : shelf } // shelf -> number

We want a number representing the number of books on my shelf. Makes sense! What about the purpose statement?

If we look at the signature for a shelf, we can see that it’s one of two things, an empty shelf "OR" a book with neighboring books. We have to describe what to do in each case.

// Tells how many books are in the shelf. If the shelf is an // emptyShelf... If the shelf is a book with neighbors (the rest of // the shelf)...

Let’s look at the first case, emptyShelf. How many books are on an

empty shelf? None! countBooks should return "0" if it’s called with

an emptyShelf. This first case is known as a "base case". The base

case of a recursive function is an input simple enough that the

function can return a result right away. (I’m mentioning that this is

a recursive function for the first time here?)

What about the other case? This is the case that is not simple enough yet. So we have to find a way to "break" the input into something smaller or simpler. How can we break up a shelf? Since we know the shelf isn’t empty (we already handled that case), we know the shelf has two parts: a book and the book’s neighbors. We’ll break up the shelf and do something with each part.

// If the shelf is an emptyShelf, then I don't have any books, the // count is 0. If the shelf is a book with neighbors (the rest of the // shelf), then (do something) with the book and (do something) with // the neighbors.

The something we want to do with this function is count. So we can count the book, and count the neighbors. But how do we get a single number out of that? We add the counts together.

// If the shelf is an emptyShelf, the count is 0. If the shelf is a // book with neighbors (the rest of the shelf), then return the count // of the book and count of the neighbors added together.

Is there a simpler way of saying that? Well, counting a single book is always going to give you the same answer — 1!

// If the shelf is an emptyShelf, the count is 0. If the shelf is a // book with neighbors (the rest of the shelf), then return "1" added // to the count of the neighbors.

This is a good purpose statement for countbooks.

So how do we write a template for this? Our input is a shelf. A shelf

is a little bit like a boolean in a way — it can be one of exactly

two things, an emptyShelf or a book with neighbors. So just like

with booleans, we can create a template with an if statement because

we know we’ll have to handle both cases.

function countBooks (shelf) { if (_.isEqual(shelf, emptyShelf)) { // if it's empty } else { // if it's not empty, we might need `shelf`'s fields: shelf.book; shelf.neighbors; } return 0; }

function countBooks (shelf) { if (_.isEqual(shelf, emptyShelf)) { // if it's empty } else { // if it's not empty, we might need `shelf`'s fields: shelf.book; shelf.neighbors; } return 0; } shouldEqual(countBooks(emptyShelf), 0); shouldEqual(countBooks(books), 3);

Okay, looking at the problem statement, I already know one branch:

function countBooks (shelf) { if (_.isEqual(shelf, emptyShelf) { return 0; } else { shelf.book; shelf.neighbors; } return 0; }

If you add this branch and run the tests, you’ll find that the one for an empty shelf is still passing! The other is also still failing, but the point is we didn’t break it any worse. :)

The other branch is not so easy. The secret is the same as what we used to model our data: recursion. To describe a bookshelf in the signature, we named the overall structure so that we could later reference it inside of its definition. We can do the same inside our function!

Our whole function is named countBooks, but we can also use

countBooks inside of countBooks.

So let’s try that! The branch for emptyShelf, our base case, is working already, so we’ll leave that alone.

The template gave us a couple things to work with here, the fields of

shelf, shelf.book and shelf.neighbors. Let’s look back at the

purpose statement.

"If the shelf is a book with neighbors (the rest of the shelf), then return "1" added to the count of the neighbors."

How can we find the count of the neighbors? Well, if our function was

working correctly, we could use countBooks! Then our purpose

statement says we just add "1" to that.

function countBooks(shelf) { if (_.isEqual(shelf,emptyShelf) { return 0; } else { return (1 + countBooks(shelf.neighbors)); } }

Add this branch and try the tests again! countBooks works!

To see how countBooks works with recursion, try "stepping through" it here:

interactive step-through of the countBooks function

Finding a book!

Let’s do a couple more exercises to better understand our bookshelf.

EXERCISE: Can you write a function called firstBook that takes a shelf and returns the left-most book on the shelf?

A firstBook function doesn’t require any recursion (it’s only

accessing the book field), but what about lastBook? Can you look

at the structure of our bookshelf data and guess how we could

determine the right-most book on a shelf?

This solution does require recursion.

Here’s the signature for this function:

// shelf = emptyShelf OR { book : { title: string, // author : {first: string, last: string} // }, // neighbors : shelf } // shelf -> { title: string, // author : {first: string, last: string} }

Just like firstBook, it takes a shelf and returns a book. Now for the problem statement:

// Finds the last book on the shelf. If the shelf is an emptyShelf, // then there is no last book -- throw an error. Otherwise, if // it's a book with no right-hand neighbors, that book must be the end // of the shelf. If it's a book that does have neighbors, then return the // last of the neighboring books.

This function has the same input, so the template is almost the same

as countBooks. But now we know that recursive functions will call

themselves, so we can add that to the template and

function lastBook(shelf) { if (_.isEqual(shelf, emptyShelf)) { // if it's empty } else { // if it's not empty, we might need `shelf`'s fields: shelf.book; shelf.neighbors; // and we're going to use lastBook as well! lastBook; } return shelf.book; // definitely return a book } //shouldError(lastBook(emptyShelf)); <- this function does't exist yet, oops shouldEqual(lastBook(books), { title: "Left Hand of Darkness", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" }});

Now all we have to do is follow the directions from the purpose statement:

function lastBook (shelf) { if (_.isEqual(shelf, emptyShelf)) { throw Error("Can't find the last book on an empty shelf!"); } else { if (_.isEqual(shelf.neighbors, emptyShelf)) { return shelf.book; } else { return lastBook(shelf.neighbors); } } } //shouldError(lastBook(emptyShelf)); <- this function does't exist yet, oops shouldEqual(lastBook(books), { title: "Left Hand of Darkness", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" }});

EXERCISE: Finding a book by title. Can you write a function

findBook(title) that takes a string and finds a book with a title

matching that string?

THINK ABOUT IT: We have first and last books — what about secondBook or thirdBook? What about these functions is different from lastBook? This introduces a new idea (accumulators) so we should probably work on it together!

Changing shelves

Another example, in a little less detail: Removing a book from a shelf — an exercise that returns a bookshelf!

Signature, problem statement, and template:

// shelf = emptyShelf OR { book : { title: string, // author : {first: string, last: string} // }, // neighbors : shelf } // string, shelf -> shelf // Removes a book with a given title from the shelf. If the shelf is empty, // return the shelf. If the shelf is a book and some neighbors, then if the // book has the same title, just return the neighbors. If the book doesn't have // the same title, then the shelf has that book, but we still need to remove // book from the neighbors. function removeBook (bookTitle, shelf) { bookTitle; if (_.isEqual(shelf, emptyShelf)) { // if it's empty } else { // if it's not empty, we might need `shelf`'s fields: shelf.book; shelf.neighbors; // and this is not the "base case" so we might need: removeBook; } return shelf; }

shouldEqual(removeBook("Left Hand of Darkness", emptyShelf), emptyShelf); shouldEqual(removeBook("Left Hand of Darkness", books), { book: { title: "The Disposessed", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: { book: { title: "Lathe of Heaven", author: { first: "Ursula K.", last: "LeGuin" } }, neighbors: endOfShelf } }); shouldEqual(removeBook("Wizard of Earthsea", books), books); // I don't own Wizard of Earthsea, so "removing" it doesn't change my shelf! function removeBook (bookTitle, shelf) { if (_.isEqual(shelf, emptyShelf)) { return shelf; } else { // if it's not empty, we might need `shelf`'s fields: if (bookTitle === shelf.book.title) { return shelf.neighbors; } else { return { book: shelf.book, neighbors: removeBook(bookTitle, shelf.neighbors) }; } } }

Not just for books

Recursive structures are a very very powerful programming concept! The more general term for the recursive structure of our bookshelves is "linked list". We can use the same ideas with any collection that can be represented as a list. Since lists are very very common, we’ve added some functions to the tlc.js library:

prefix(item, list) will add some item to the beginning of some list.

You can create a list of strings by doing this:

prefix("first string", prefix("second string", prefix ("third string", emptyList)));

You can also make lists of numbers:

prefix(1, prefix(2, prefix (3, emptyList)));

You can make a list of your cats:

prefix({name: "Macgonagall", age: 4}, prefix({name: "Haskell", age: 3}, emptyList));

prefix(circle(20, "red"), prefix(rectangle(40, 60, "blue"), prefix(text("hello", 12), emptyList)));

We’ve also added head and tail functions that are a little like

"firstBook" and "neighbors". head(list) gets the first item in a

list. tail(list) gets the rest of a list.

var listOfImages = prefix(circle(20, "red"), prefix(rectangle(40, 60, "blue"), prefix(text("hello", 12), emptyList))); shouldEqual(head(listOfImages), circle(20, "red"));